Sweden remains the only country in the world to still uphold the institution of fideikommiss—entitled estates, a system in which standard inheritance laws do not apply, and where estates have traditionally been passed down exclusively to the eldest son. Why has this archaic form of inheritance persisted here, long after being abolished elsewhere in Europe? Historians at Lund University offer some compelling explanations to fideikommiss in Sweden.

In their article “Between Deplorable Anachronism and Valuable Heritage: The Persistence of the Swedish Fideikommiss Institution, 1810–1964“, Magnus Bergman and Martin Dackling explore the enduring presence of the fideikommiss in Sweden, long after similar institutions were abolished across Europe. Fideikommiss refers to entailed estates that are inherited by a single heir, typically male, and are restricted from being sold or divided. In Sweden, most fideikommiss were established during the 18th century.

The authors analyze parliamentary debates and legislative actions over approximately 150 years to understand this persistence. In 1810, Sweden prohibited the creation of new fideikommiss but allowed existing ones to continue, framing them as matters of individual property rights rather than feudal remnants. This perspective contrasted with other European countries, where such estates were often viewed as outdated feudal structures subject to expropriation.

Efforts to abolish fideikommiss gained momentum in the early 20th century, particularly around 1914, with intentions to implement land reforms favoring small-scale farming. However, shifting agricultural trends and economic considerations led to the postponement of these reforms. By the 1950s, many fideikommiss estates were recognized for their efficient management and cultural significance, leading to a nuanced approach in the 1964 abolition law. This legislation aimed to dissolve the fideikommiss system while preserving the estates’ cultural and economic contributions.

Bergman and Dackling’s study highlights the complex interplay between legal frameworks, economic shifts, and cultural perceptions that contributed to the prolonged existence of fideikommiss in Sweden, offering insights into how historical institutions can persist amid evolving societal values.

Remaining fideikommiss in Sweden

Thirteen fideikommiss remain in Sweden:

- Mindre Ankarcronska, Danderydsgatan 8

- Björnstorp and Svenstorp

- Boo

- Christinehof, Högestad

- Erstavik, Munkbron

- Fullerö

- Heby

- Koberg and Gåsevadholm

- Näsbyholm

- Refvelsta, Göksbo

- Sturefors

- Trolle-Ljungby and Årup

- Övedskloster

Are you curious to learn more about the remaining fideikommiss in Sweden? Visit fidiekommiss.se! Behind the website stands Fideikommissariernas Intresseorganisation—the Interest Organization of the Fideikommiss Holders. It serves as a representative body for the remaining Swedish fideikommiss estates and fideikommiss-based limited companies, working to safeguard their interests and promote awareness of this unique heritage.

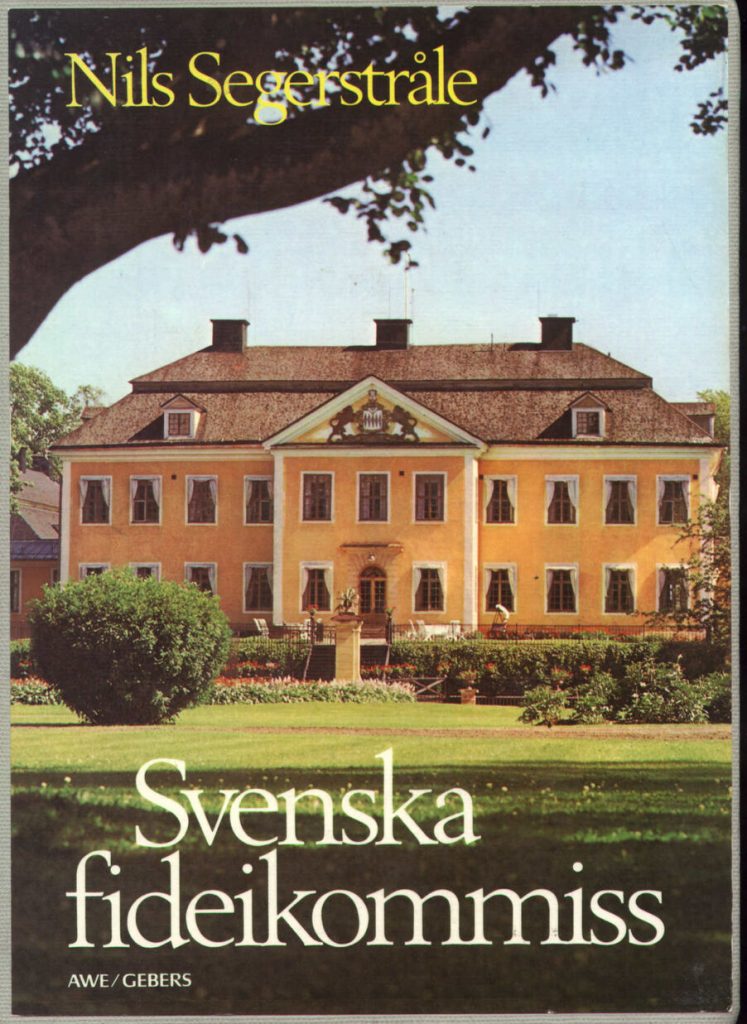

I also recommend reading Nils Segerstråle’s book “Svenska fideikommiss” from 1974, available on Project Runeberg.

Photo: Pål-Nils Nilsson / Kulturmiljöbild, Riksantikvarieämbetet