Suecia Antiqua et Hodierna (Latin for “Ancient and Modern Sweden”) is a monumental work that provides a detailed topographical account of 17th-century Sweden. Created by the Swedish military engineer and architect Erik Dahlbergh, it contains over 350 copper engravings that document the country’s cities, castles, estates, parks, and historical landmarks – a visual representation of Sweden at the height of the Swedish Empire.

The upward mobile Erik Dahlbergh

Erik Dahlbergh was born as Erik Jönsson on October 10, 1625, in Stockholm to parents belonging to the peasant class. At the age of four, Dahlbergh lost his father. His mother remarried a lieutenant from the Västmanland regiment but six years later, she too passed away. The ten-year-old orphan boy then lived as a foster-child with his stepfather’s relatives in Söderköping. He completed his grade school in Sweden at the age of twelve. His uncle and guardian arranged for the young Dahlbergh to travel to Hamburg for vocational training, which equipped him to undertake clerical duties.

Upon completing his studies, he was offered a position in the provincial administration of Pomerania. Dahlbergh worked in Stettin – then capital of Swedish Pomerania – for six years as a clerk under the general treasurer of Pomerania, Gert Rehnskiöld. Rehnskiöld had early recognized Dahlbergh’s aptitude for mathematics and exceptional talent for drawing, and consequently recommended him for training as a fortification engineer. Keep in mind that the Thirty Years’ War was still raging across Europe at this time.

After the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, which put an end to the Thirty Years’ War, Dahlbergh was sent to Frankfurt to manage war reparations. He spent three years in Frankfurt. Upon finishing his assignment, he traveled through Europe before returning to Stockholm in 1654. He then chose, after being passed over for a military appointment, to tutor two young Swedish noblemen on their peregrination – a Grand Tour, a practice of the aristocracy at the time – which took him to many of the great cities of Europe. During his travels, he met the future court painter David Klöcker (later knighted Ehrenstrahl), and the two formed a lifelong friendship while encouraging each other’s careers.

Following Charles X’s invasion of Poland in 1655, Dahlbergh was assigned to plan and construct front-line fortifications. He accompanied the king throughout the campaign, documenting military activities and overseeing the construction of defensive works. He also played a key role in the 1657–1658 invasion of Denmark, assessing ice conditions for the troops’ famous march across the frozen Little Belt. After hostilities ended and Charles X passed away, Dahlbergh was promoted to First Lieutenant in the Södermanland regiment and knighted, adopting the surname Dahlbergh. Between 1667 and 1668, he undertook diplomatic missions to Germany, the Netherlands, France, and England, before being appointed commander of the forces in Malmö. In September 1674, he was given full responsibility for all fortifications in Sweden.

Dahlbergh’s career continued to progress, and by 1693, he had attained several prominent positions, including chief administrator of Bremen, Verden, and Livland, the newly annexed territories. In 1702, he formally requested to be relieved of his duties, nine months prior to his death on January 16, 1703.

He married Maria Eleonora Drakenhielm in 1666, and together they had eight children. She passed away at the age of 30, and only two of their daughters survived him, resulting in the extinction of his lineage upon his death.

Erik Dahlbergh’s Suecia Antiqua et Hodierna

The idea of Suecia Antiqua et Hodierna was conceived by Dahlbergh himself and presented to the Crown. Erik’s direct source of inspiration was the topographical publications issued by Merian, such as Theatrum Europeum and Topographia Galliae. Dahlberg wished to see the same type publication for Sweden. On March 28, 1661, Erik was granted an exclusive privilege by the minority council of Charles XI to publish his planned large-scale topographical work on Sweden, the renowned work Suecia antiqua et hodierna, illustrated with engravings based on Dahlbergh’s own drawings. The engravings were intended to be accompanied by informative text.

Following the decision of the Crown, Erik continued diligently, during his many travels across Sweden in the 1660s, to draw notable cities, churches, castles, manor houses, and more.

At the same time, by royal command, Uppsala professor and royal historiographer Johannes Loccenius worked on the text, which was to be in Latin. He managed to compile descriptions of landscapes and towns before passing away in 1667.

After receiving funding from the Crown, Dahlbergh traveled in the summer of 1667, via Holland and England, to Paris to hire skilled engravers – Jean Marot, Jean Lepautre and the brothers Nicolas and Adam Perelle – for the reproduction of his completed drawings for Suecia Antiqua et Hodierna. Upon his return, Dahlbergh managed the engraving work in Paris through correspondence with his representative there, Samuel Agriconius.

After his appointment as general quartermaster in 1674, work on the Suecia Antiqua et Hodierna almost entirely ceased for the next ten years. The reason for this was the reconstruction of the kingdom’s many dilapidated fortifications.

In 1684, an important decision was made in the history of the project: Charle XI had decreed that the state would sponsor Dahlbergh’s work. Dutch engravers, such as Herman Padtbrugge, Willem Swidde and Johannes van den Aveelen, who had been summoned to Sweden, were now employed for this purpose.

It had now been over twenty year before a new author of the texts was found in the form of state historian Claudius Örnhielm in 1690. He coined the title and wrote seven of the twelve chapters intended for the first volume of the seven-volume work before he died in 1695. Eventually, the professor in Eloquence and Government from Uppsala, Petrus Lagerlöf, was assigned the task and worked to the best of his ability for as long as he could. After his death, the task was entrusted to Olof Hermelin, and later Bengt Högvall and Samuel Auséen, neither of whom produced anything substantial. By this point, in 1703, Erik Dahlbergh had also passed away.

Finally released – after 60 years

In 1702, just months before Dahlbergh’s death, the state administration took over responsibility for Suecia Antiqua et Hodierna, much to Dahlbergh’s dismay. After 1715, due to a lack of institutional support, no further progress was made on the project. Dahlbergh’s materials were stored in the National Archives, where, by the late 1720s, in the wake of the Great Northern War, their potential was recognized as a means to help reduce the national debt. A preliminary edition of 600 copies—without text—was produced and put up for sale in 1729 or 1730.

By that time, Sweden’s era of great power had come to a bitter end, and the images no longer held the same immediate relevance. However, their value and significance have only grown with time. For modern-day Swedes, Suecia Antiqua et Hodierna offers an invaluable window into the nation’s history. Its images, primarily from the period of King Charles XI’s regency, capture the ideals and grandeur of that era.

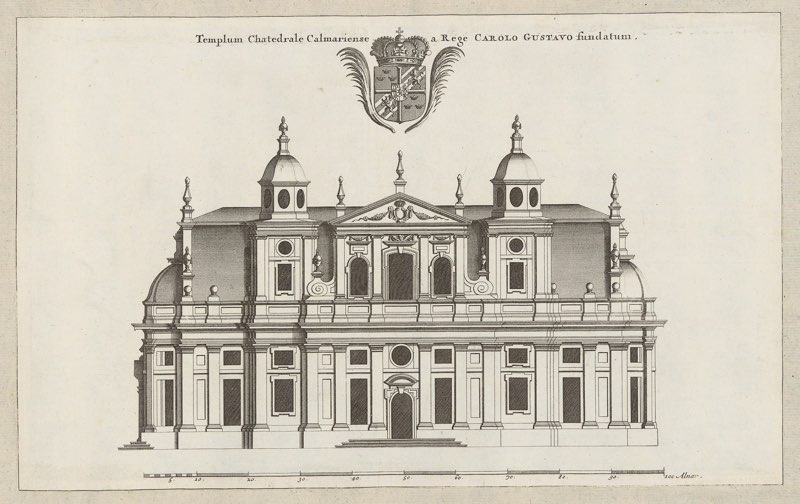

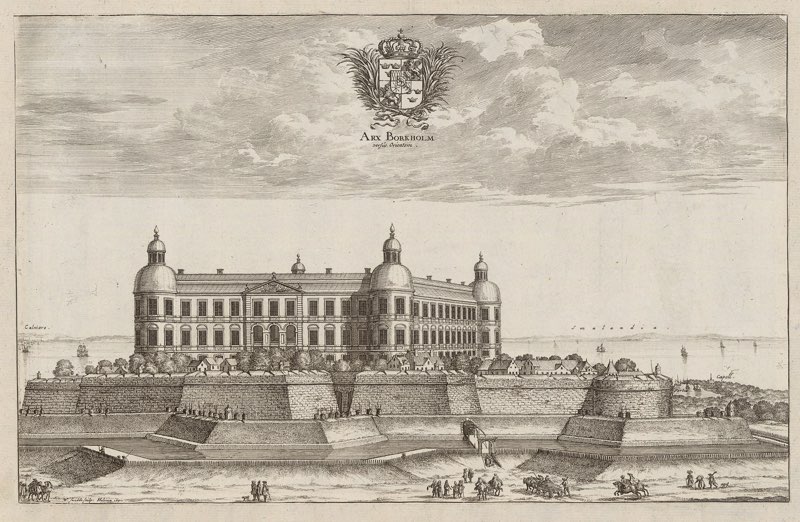

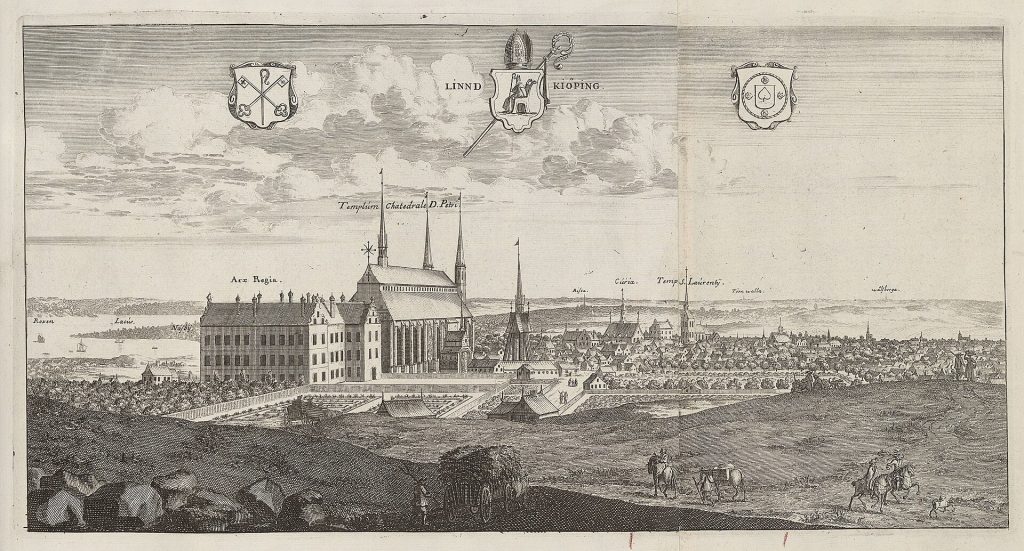

The work was created with the aim of raising Sweden’s image across Europe. To this day, it remains unparalleled as the most significant work of its kind ever published in Sweden. It contains 353 illustrations—90 of which depict cities across Sweden, including Finland and Pomerania; 230 showcase castles, manor houses, and parks, while the remaining illustrations feature historical sites, churches, maps, coats of arms, portraits, and more.

Fact or fiction?

Many of the images in Suecia Antiqua et Hodierna are documentary, while others are imaginary or contain ideal buildings. For example, some of the images of manor houses served as preliminary renderings of how the aristocratic landowners envisioned the future reconstruction of their estates, though many of these plans were never realized. Additionally, important buildings are often depicted with exaggerated proportions, making them appear larger than they actually were. As a result, their historical accuracy is somewhat limited. For most of its citizens at the time, Sweden likely did not appear as it is depicted in Suecia Antiqua et Hodierna.

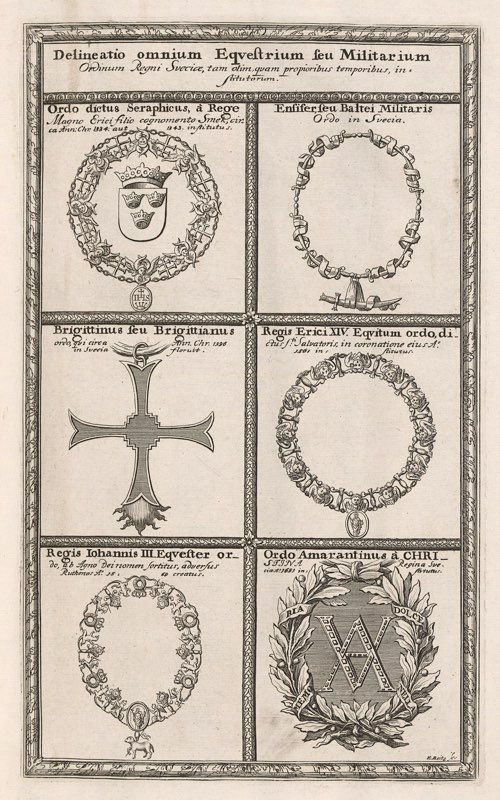

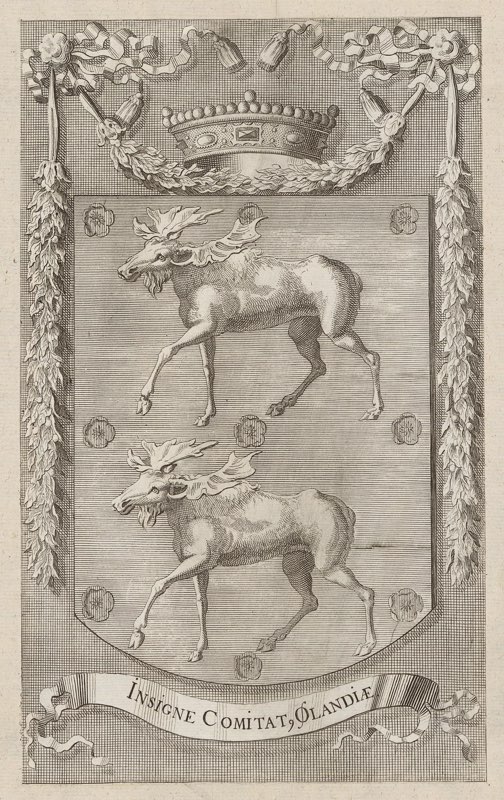

Suecia Antiqua et Hodierna offers much more than just images of buildings, cities, and landscapes. For a heraldic scholar, it holds a wealth of interest, as it features numerous coats of arms.

Below is the coat of arms of Öland. Öland’s coat of arms was represented in the procession at Gustav Vasa’s funeral in 1560. The first depiction appears in the Parishandskriften from 1562, where the stag, however, lacks a collar and has a different color for its adornments. In 1569, the dowager queen Katarina Stenbock was granted Åland as a fief. From this point onward, this region also adopted a coat of arms—two roe deer above each other, possibly with a field strewn with roses. Early on, these similarly named regions were confused, and in the 1880s, Öland’s coat of arms was established as two roe deer and nine roses. However, during the revision of arms in 1944, the order was restored, and in the coat of arms description, the stag was provided with a collar to signify royal game.

Suecia Antiqua et Hodierna has been digitalized by the National Library of Sweden and is available here.

Source: Suecia